President Bush visited Hanoi last week as part of a three-day Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit.

Our President was asked about the "lessons of Vietnam" in relation to our involvement in Iraq.

He

stated:

"Yes, I mean, one lesson is, that we tend to want there to be instant success in the world, and the task in Iraq is going to take a while,''' he said. "But I would make it beyond just Iraq. I think the great struggle we're going to have is between radicals and extremists versus people who want to live in peace, and that Iraq is a part of the struggle. And it's just going to take a long period of time to -- for the ideology that is hopeful, and that is an ideology of freedom, to overcome an ideology of hate. "Yet, the world that we live in today is one where they want things to happen immediately,'' he said. "And it's hard work in Iraq… We'll succeed unless we quit.''

Were these the real lessons of Vietnam?

That we could succeed "unless we quit"? Was this the extent of his understanding? That our ideology of "freedom" was struggling to overcome an ideology of "hate"?

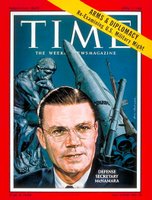

Robert McNamara was Secretary of Defense during most of the Johnson Administration, and was involved in the development and implementation of Vietnam policy for this country.

Robert McNamara was Secretary of Defense during most of the Johnson Administration, and was involved in the development and implementation of Vietnam policy for this country.

In 1995, years before our current involvement in Iraq, Secretary McNamara summarized his understanding of the lessons and the reasons behind our failure in Vietnam.

McNamara stated:

"The important point is the decision was ours, not Eisenhower's. And we were wrong. We made the decision; he didn't make the decision. And to demonstrate how and why we went wrong, I review in key detail the key decisions that we faced over the ensuing seven years. And I discuss each of them. What the alternatives were, how we evaluated the alternatives, why we acted as we did, what might have happened if we'd chosen a different alternative. And it's from that review that I identify our failures, and it's from that review that I draw from the lessons, which I believe will be applicable and relevant to the 21st century. Now, I'm going to go through. There are eleven of them."

He states:

"The first point is we misjudged them, and I think we're misjudging today the geo-political intentions of our adversaries. In that case, it was the geo-political intention to North Vietnam and the Viet Cong supported by China and the Soviet Union. And we exaggerated the dangers to the U.S. of those adversaries. And I think we're continuing to do that."

Perhaps instead of the "domino theory", we are frightened into supporting this war with the lie that we will have to fight them here if we aren't fighting them there!

As Vice-President Cheney frequently points out:

"We can't guarantee there won't be another one, obviously, but we've gone over four years now. And I think it's been because we've been fighting them on their turf instead of having to fight them here on the streets of our own cities."

McNamara continued:

"Second mistake. We viewed the people and leaders of South Vietnam in terms of our own experience. We're still doing that. We saw them as having a thirst for a determination to fight for freedom and democracy. We totally misjudged the political forces within that country."

Again, we have made the same mistake. As President Bush himself stated after the last Iraq elections:

"Our efforts to advance freedom in Iraq are driven by our vital interests and our deepest beliefs. America was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and we believe that the people of the Middle East desire freedom as much as we do. History has shown that free nations are peaceful nations. And as Iraqi democracy takes hold, Iraqi citizens will have a stake in a common and peaceful future."

Do Iraqis really believe that all men are created equal? Are we reading into Iraq our own values? The answers are obvious.

Again, back to McNamara:

"Thirdly, we underestimated the power of nationalism to motivate people. In this case, the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong. Then we underestimate the power of ... (inaudible) to motivate a people to fight and die for their people."

and

"Fourthly, our misjudgments of friend and foe alike reflected our profound ignorance of a history, culture and politics of the people in that area, and the personalities and habits of their leaders."

As reported on RAW STORY:

"In his new book, The End of Iraq: How American Incompetence Created A War Without End, Galbraith, the son of the late economist John Kenneth Galbraith, claims that American leadership knew very little about the nature of Iraqi society and the problems it would face after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein.

A year after his “Axis of Evil” speech before the U.S. Congress, President Bush met with three Iraqi Americans, one of whom became postwar Iraq’s first representative to the United States. The three described what they thought would be the political situation after the fall of Saddam Hussein. During their conversation with the President, Galbraith claims, it became apparent to them that Bush was unfamiliar with the distinction between Sunnis and Shiites.

Galbraith reports that the three of them spent some time explaining to Bush that there are two different sects in Islam--to which the President allegedly responded, “I thought the Iraqis were Muslims!”

McNamara continued:

"Fifth, forsaken lesson. We failed then as we have since to recognize the limitations of modern high technology military equipment and forces in doctrine in confronting unconventional highly motivated people's movements."

As Dan Baum wrote in the New Yorker in January, 2005:

"In Iraq, the Army’s marquee high-tech weapons are often sidelined while the enemy kills and maims Americans with bombs wired to garage-door openers or doorbells. Even more important, the Army is facing an enemy whose motivation it doesn’t understand. “I don’t think there’s one single person in the Army or the intelligence community that can break down the demographics of the enemy we’re facing,” an Airborne captain named Daniel Morgan told me. “You can’t tell whether you’re dealing with a former Baathist, a common criminal, a foreign terrorist, or devout believers.”

McNamara continued:

"Sixthly, we failed and we came damn close to making this mistake in connection with the Gulf War. We failed to draw Congress and the American people into a full and frank discussion and debate of the pros and cons of large scale U.S. military involvement."

"And seventh, after the action got underway, and unanticipated events forced us off our planned course, we fail to retain popular support, in part, because we hadn't explained fully what was happening and why we had to do what we did."

The support for the Iraq war continues to plummet. As reported four days ago:

"Washington | Americans' approval of President Bush's handling of Iraq has dropped to the lowest level ever, increasing the pressure on the commander in chief to find a way out after nearly four years of war.

The latest Associated Press-Ipsos poll found just 31 percent approval on his handling of Iraq, days after voters registered their displeasure at the polls by defeating Republicans across the board and handing control of Congress to the Democrats. The previous low in AP-Ipsos polling was 33 percent in both June and August.

Erosion of support for Bush's Iraq policy was most pronounced among conservatives and Republican men - critical supporters who propelled Bush to the White House and a second term in 2004."

Back to McNamara:

"Eight, we didn't recognize that neither our people nor our leaders are on a mission. To this day we seem to act in the world as though we know what's right for everybody. We think we're on a mission. We aren't. We weren't then and we aren't today. And where our own security is at stake, I'm prepared to say act unilaterally, militarily. Where our security is not at stake, not directly at stake, narrowly defined, then I believe that our judgement of what is in another people's interest, should be put to the test of open discussion, open debate, and international forum. And we shouldn't act unilaterally militarily under any circumstances. And we shouldn't act militarily in conjunction with others until that debate has taken place. We don't have the God-given right to shape every nation to our own image."

and

"Ninth, we didn't hold to the principal that U.S. military action other than in response to direct ... (inaudible) to our own security should be carried out only in conjunction with international forces who are going to share in the cost. And I don't mean financial cost, although I certainly include financial cost, but I mean primarily the blood cost, the blood risk."

and

"Tenth, we failed to recognize that in international affairs, as in other aspects of life, there may be problems which there are no immediate solutions, certainly no military solutions."

"And finally underlying many of these ten mistakes lay our failure to organize the top echelons of the executive branch to deal effectively with the extraordinarily complex range of problems that we were facing. Political issues, military issues."

No Mr. President. The lesson of Vietnam was far more complex than we can succeed if we don't quit.

The lessons include not trying to impose our way of life on others who might not share our cultural values. Includes understanding what those cultures are before we get there. Not assuming that high tech can defeat low tech as we have learned from the deaths from IED's. Not lying to Americans about WMD's or 'fixing the facts' to get us involved in the conflict. Not attacking with our military when we were not militarily at risk. And maintaining the communication and cooperation with Congress to maintain support for this effort.

No Mr. President, our failure is much due to your failures. And Americans continue to pay the ultimate cost.

We need a new direction in America. Senator Kerry understands what it means to send an American to die for a mistake. Senator Kerry supports our soldiers in ways far more real than the neoconservative cheerleading for "victory". He may not be able to tell a joke.

But he can tell the truth.

Bob